Photo credit: Rachel Adams

Ways Out of the Trauma Parade

“I have certainly seen [that] there are the people who only want the autism from me and then there’s people who say they don’t only want the autism from me but magically it’s only the autism pitches that get accepted.” — Sarah Kurchak

“The institutions won’t change unless not changing will cost them, right? Like, they have to be either shown a carrot or a stick and unfortunately in journalism they almost only ever respond to the stick.”

Those are the words of Christopher Curtis, editor-in-chief and co-founder of digital news outlet The Rover. During his time at the daily Montreal Gazette—prior to his going independent—although he believed his colleagues were supportive of his mental health needs, those needs were more valid if he could fuel them into content. What changed? A series of cat-related TikToks he created drew attention as he highlighted the weight of mental health conditions during a time of incredible stress.

“I really didn’t feel like anyone at the Gazette ever took it seriously,” he said, referring to his mental-health. “And then, all of a sudden, my very serious mental health condition gets them a bit of attention and then it’s okay.”

Many journalists, whether they identify as disabled or not, face a similar conundrum: write about your trauma and risk being pigeonholed or hide it. While data about Disabled journalists is sparse—for many reasons, including the fact that newsrooms are often unsafe places to identify publicly—feeling that they need to shrink to fit the industry is a common one.

Despite the support he felt from mentors and colleagues, Curtis found that the structures in place—particularly health insurance —provided insufficient care in an industry that can be notoriously hard on people’s bodies and minds. He saw that the pressure to produce was always there, regardless whether his colleagues saw what he was managing when it came to his health.

“I still was expected to perform under really grueling circumstances and produce journalism for them that got them a lot of traffic and that got them a lot of acclaim. It just felt like an inconvenience to bring it up. And so I stopped and I eventually left not feeling supported,” Curtis said.

And this isn’t just an editing problem.

For Curtis and others willing to talk frankly about their health publicly, one of the biggest challenges of working in newsrooms is the expectation they share their lived experience to produce trauma porn for clicks. They add that this tension is a huge source of conflict, internally and externally, which leads to large gaps in coverage and a subset of journalists who are not reaching their career goals.

A matter of agency

Sarah Kurchak, an autistic journalist and author, at times has pigeonholed herself to pay the bills.

“I will exploit myself if I need to pay the rent a little,” she said.

Kurchak, who has written about everything from wrestling to Canadian music to fitness, said that she’s seen how people treated her differently before and after her diagnosis.

“I have certainly seen [that] there are the people who only want the autism from me and then there’s people who say they don’t only want the autism from me. But magically it’s only the autism pitches that get accepted,” she said.

Forbes Advisor’s Christopher Groux made a conscious decision not to disclose his disability until he felt it increased the credibility of his coverage. In that way, he hasn’t felt pigeonholed but acknowledges that his disability has undoubtedly shaped his career.

“During probably three-fourths of my career I didn’t really mention my disability. I didn’t want employers to think I was less capable. So I charted my path without it — ’til I was asked to review ‘The Last of Us Part II’ and was blown away by the accessibility options on display. But I wanted my assessment to be taken seriously, so I disclosed my disability at that point,” Groux said.

Plus, there’s another career concern to balance: Many newsrooms limit journalists who write opinion pieces from writing news and feature stories on the same topic. The Tyee’s Andrea Bennett, said they kept part-time jobs outside of journalism during their freelance days to maintain flexibility. They shared that part of preventing being pigeonholed was keeping in mind what doors potentially closed when they agreed to write an opinion piece.

“If you write a bunch of op-eds from whatever your positionality is, that editorially affects whether or not you can really be assigned, let’s say, a long-form investigative feature in that area. There’s some nuance there, but I’ve kept that in mind too: What do I want to be able to cover in that long investigative-feature way?”

While the journalists DJA spoke with all live in North America, this is far from just a U.S. or Canada phenomenon.

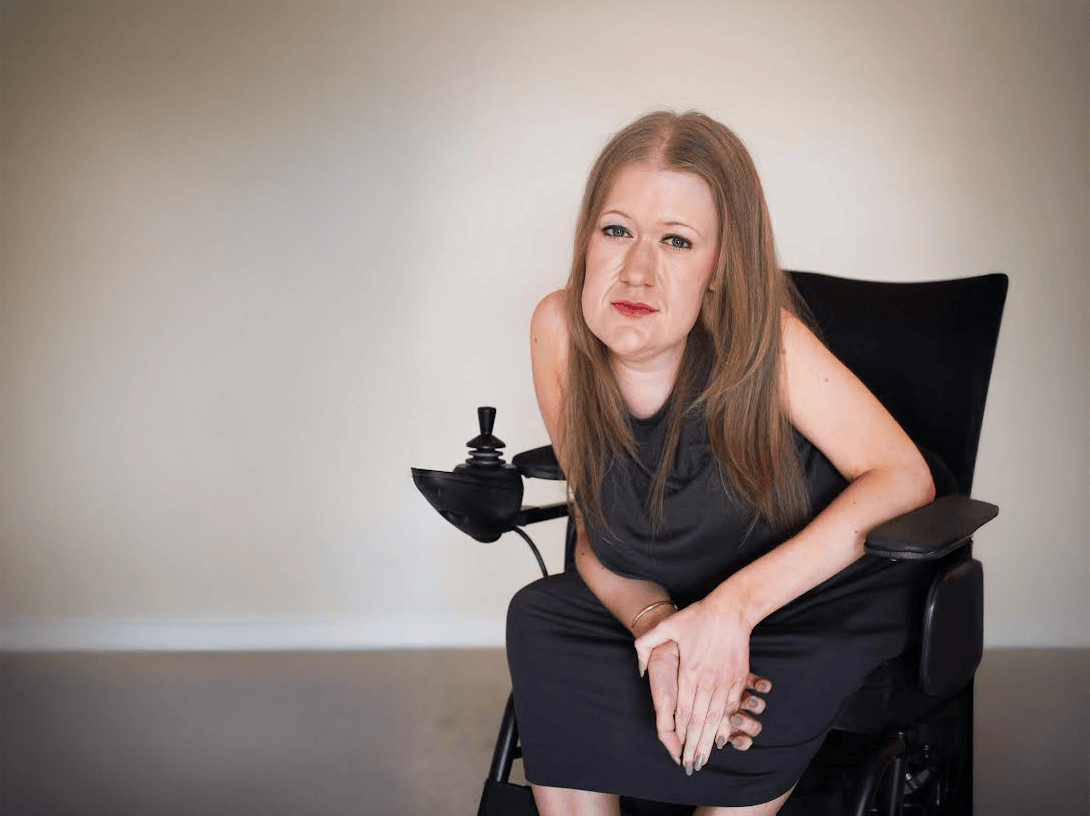

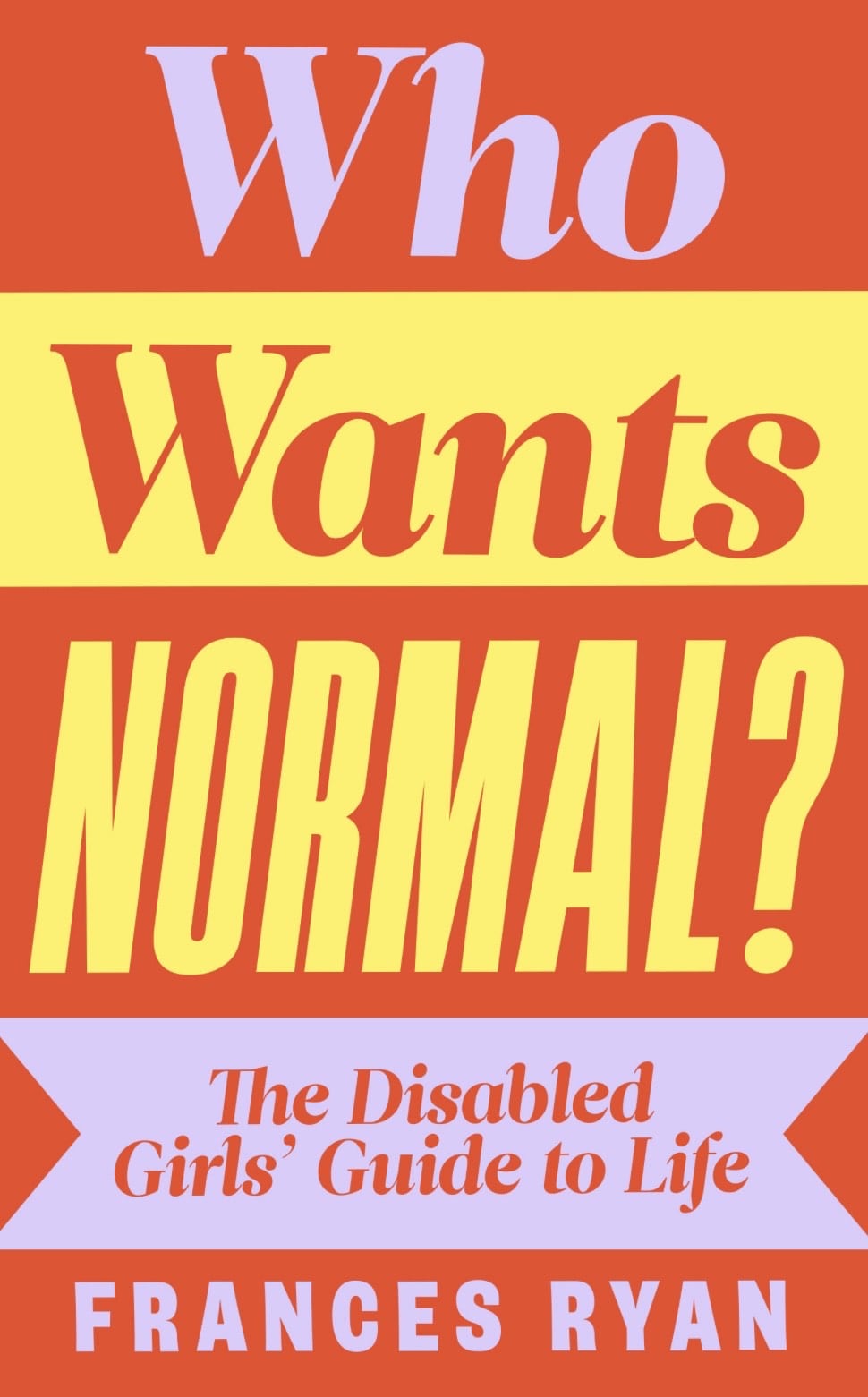

Frances Ryan is a columnist with The Guardian and author of multiple books, including Who Wants Normal?, in which she shares how it feels to be Disabled facing the reality of being hemmed into one version of a journalist.

She writes: “When I first started working as a journalist, I was only called by a producer or editor when they needed to talk about disability. Fifteen years into my career, I’m still often labeled The Guardian’s ‘disability columnist’ despite this role not existing at the paper and my work focusing on politics. Call it the segregation of disabled journalists: while non-disabled presenters and creatives are offered roles across a range of subjects and genres, their disabled colleagues are often pigeonholed for work focused on disability.”

So, how do journalists resist?

Although the thought Disabled journalists never escaping the endless loop of excavating their trauma for a few clicks and a handful of coins may seem dire, the journalists we spoke to for this story prove otherwise.

Curtis leads incredible coverage about political and environmental strife in Indigenous communities. Kurchak’s work has simultaneously called out the wrongs of ableist television shows and entertainment magnate Vince McMahon.

Groux has led product-review coverage during a groundbreaking role at USA Today, while bennett’s work for The Tyee has spanned politics, sheep-shearing and doomsday prepping, to name just three.

As a senior editor, bennett’s advice for those looking to avoid being pigeonholed into a certain style of op-ed by assigning editors is to politely decline and to tell them that you have a strong pitch that you’ll contact them about soon. Another option they suggested is to decline and recommend someone else. Regardless of how you approach it, bennett said that breaking out of the op-ed space requires doing extra to prove yourself, including putting significant effort into crafting pitches.

“If they see you as someone who is writing from personal experience, then you’re probably going to need to have to do that much more work to show that you also have those reporting tools,” bennett said.

For Groux, the key to getting assignments beyond disability op-eds is to embrace the direction journalism is trending—particularly digitally.

“It’s important to advocate for yourself,” Groux said. “Explain why, from your perspective as a Disabled person, your version of the content is the most effective choice. Google is prioritizing the individual authority of authors more than ever. Lean into that. Work with editors to modify pitches into the content you want to make.”

For Kurchak, one form of resistance is to push back when an editor asks for a particular version of your own identity: “It’s going to be hard. It’s going to be painful. You’re going to be tired and want to just say no, but fight back against the first-person book-report identity paragraph because I think we all deserve better than that as writers and readers.”

As for what that carrot-and-stick approach might look like, Curtis suggests strategies like self advocating within the newsroom, getting in touch with your union if you’re in a unionized environment or, barring that, speaking to a journalist from outside your newsroom about what you’re going through.

Curtis described what progress might look like for news organizations: “[It] is devoting time, resources, ad space [and] column inches to better understanding the perspective of Disabled journalists. And in the same way that we talk about diversity in the newsroom, which is essential, we need for that to be true diversity.”

More DJA Coverage

There is a dearth of coverage about the hundreds of thousands of people, including 21,000 children, who...

By

January 15, 2026

When I started working in media in 2009, at a music publication, I didn’t have the knowledge and skills I...

By

January 13, 2026

On Dec. 2, The Atlantic published a piece titled “Accommodation Nation” that calls into question the validity of some...

By

December 16, 2025