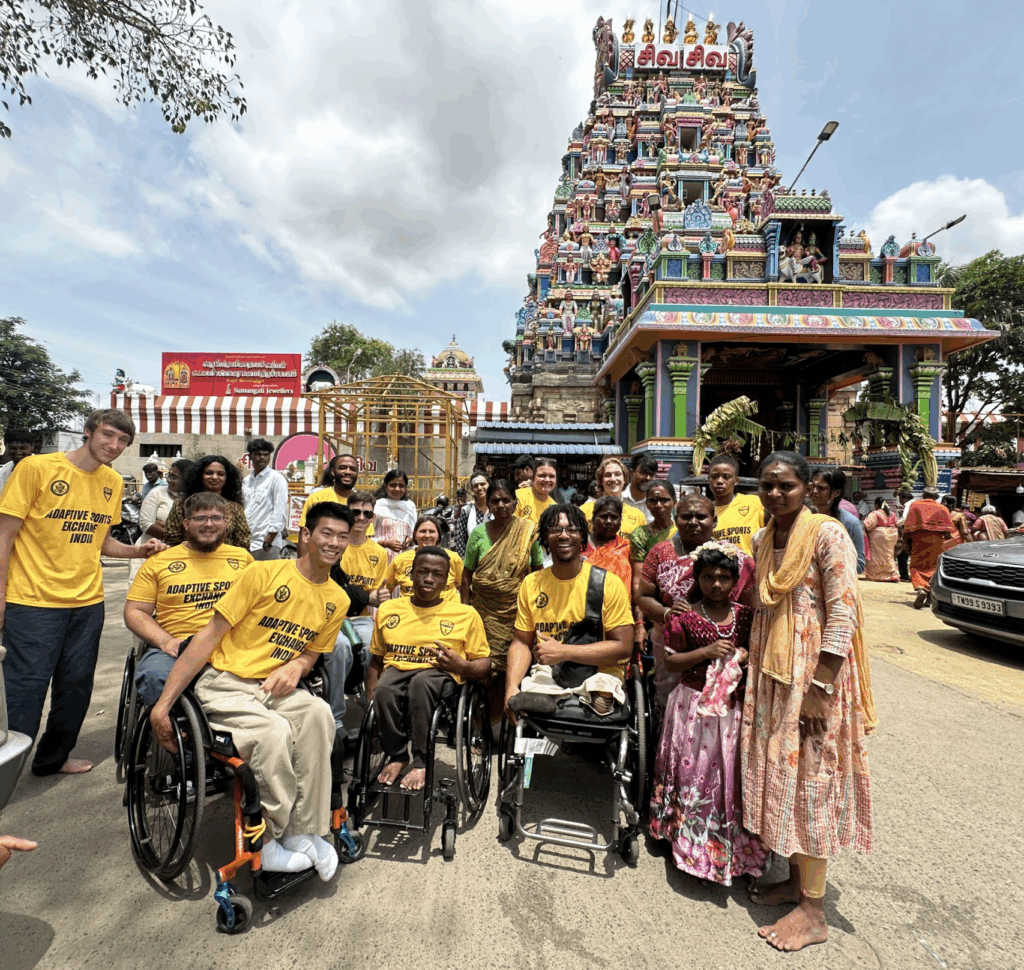

A delegation of collegiate wheelchair basketball athletes and coaches from programs in Alabama, Arizona, Missouri, Illinois and New York recently traveled to Tamil Nadu in India for an Outbound Sports and Cultural Exchange Program.

You don’t need to have been there to feel the sights and sounds of a gym half the world away. The contemplative bounce of a ball, the hushed jokes and loud heckles, the smiles and grimaces. Plus, the banging and crashing of wheelchairs.

Such was the scene from a first of its kind trip, when a delegation of collegiate wheelchair basketball athletes and coaches from programs in Alabama, Arizona, Missouri, Illinois and New York traveled to Tamil Nadu in India for the Outbound Sports and Cultural Exchange Program. The goal? A cultural swap with an opportunity to support para sport and for participants to learn more about how young Disabled people from both countries can connect, collaborate and compete.

One of the American athletes who spoke to DJA before the trip about her excitement was Morgan McCammon, who is going into her fifth year at the University of Illinois and building a coaching career while playing at the oldest collegiate para sport program in the U.S.

“It’s so much more than just sport — it’s like community, it’s inclusion, it’s so many things. I’m really excited to see that on an international level as well, and to see how sport can bring empowerment and … social change as well in a country where people with disabilities have a very different lived experience than we do in the United States,” McCammon told DJA.

It’s a tough time for American diplomacy, let alone disability-focused projects. And yet, using sports as a form of international development is far from a new concept, even within para sport circles. There is a long tradition of (largely) Western athletes and coaches traveling across the globe to help spread the sport and to support accessibility projects in developing countries.

Organizations like the International Committee of the Red Cross have dedicated staff focused on such para sport and that’s to say nothing of broader governing bodies like the International Paralympic Committee or the International Wheelchair Basketball Federation. Even the uglier side of sports diplomacy—such as the phenomenon known as sports washing—where countries with records of human rights abuses use international sporting events to launder their international reputation has hit the para sport world, with international competitions regularly scheduled in places where Disabled people are more likely to be locked away than celebrated.

In this case, Gunasekaran Jagadeesan, founder of the Sittruli Foundation and one of the host organizers, believes that the trip was beneficial not just for the athletes but for the region.

“We invited talented wheelchair basketball players from all states in South India,” he said. International gatherings of para-athletes, like this event, serve as an important boost for the sport in India.

Organizers say international gatherings of para-athletes, like this event, serve as an important boost for the sport in India.

The foundation focuses on growing adaptive sports and building a more inclusive sports culture throughout India. In the 2024 Paris Paralympics, India took home 29 medals, its most in recorded history, amping up interest in para athletics. But there’s still work to do. Sittruli aims to make sports more accessible to the disabled community. Two weekly wheelchair basketball training camps were established by the foundation in Coimbatore and Erode districts, offering regular training opportunities for athletes. Sittruli also organizes yearly awareness camps where Disabled individuals keen on sports can speak with young athletes from the foundation about table tennis, wheelchair basketball and archery and check out their gear.

“Innovation in sports wheelchairs not only makes equipment more affordable but also gives athletes the freedom and confidence to express their needs and contribute to the development of better technology,” Gunasekaran shared with DJA. The camps give athletes a chance to be involved in the events and help the foundation discover new talent like Keertika Jayachandran, a novice wheelchair basketball player who is now a national gold medalist in shot put and javelin.

Gunasekaran, a self-trained athlete himself, founded Sittruli out of his desire to uplift and empower his community. “We use sports as a universal language to spread awareness throughout the community,” he explained to DJA. As a social worker and volunteer, he understands the pain involved with being denied access to basic sports and training, especially for people with disabilities. “I believe sports is the most effective tool to empower people with disabilities and help them become rightful and active partners in society,” he shared.

The upbeat energy continued throughout the program’s activities which took place in two cities in South India — Coimbatore and Chennai. In Coimbatore, the host organizations arranged visits to local historical parks, museums and temples. “We have a packed cultural experience in store for the U.S. Team,” he told DJA before the event. At one point during the first few days, the teams were greeted in ceremonious style with a live band banging on dhols, singing and dancing on the court.

At Agrahara Samakkulam Lake, the U.S. team got a taste of local traditions like Aadi 18, a celebration of water, where they dressed in traditional Indian attire. In Chennai, they explored IIT and its Research park, Santhome Cathedral, Marina Beach, Nehru Stadium, the Museum of Possibilities, DakshinaChitra Museum, and the UNESCO World Heritage site, Mamallapuram.

For Gunasekaran, one of the biggest takeaways was the strong connection formed between the para athletes. “I specifically introduced the buddy system in the program because I know that this bond will take the program’s impact a long distance,” he told DJA. An alumni of the Global Sports Mentoring Program, Gunasekaran traveled to the University of Tennessee in 2023 for a cultural exchange program catered towards community sports. He knew how emotional such an experience can be for both teams. “We said goodbye at a farewell dinner at the Hyatt. An airport sendoff would have been too emotional. The WhatsApp group was flooded with messages, videos of dances, and emojis flying across the globe.”

Another member of the Illinois contingent was Joshua Pierce, a junior. Prior to the trip he was hopeful he could bring learnings from the places he grew up, in China and the US, when it comes to accessibility.

“The place where I grew up [in China], it was not very wheelchair accessible, and a lot of times there [were] so many stairs but those never really stopped me. So, I had other people help me together, or I had to help myself to get up to where I want to be…I wonder how they live there and, if they want, I can share some of my knowledge and maybe I will help them to live a better life even when the place is not very accessible,” Pierce shared.

No international trip made by a group of disabled people is simple. The trip was a collaboration between the U.S. State Department’s Educational and Cultural Affairs Bureau’s Sports Visitor Program, Sittruli Foundation, Tamil Nadu Wheelchair Basketball Association, and Kumarguru Institute, a private engineering college that housed participants during their visit. India, a country not known for its accessibility, with only 3% of buildings accessible by wheelchair, along with Peru were the only other outbound locations for the sports visitor exchange program. The Right of Persons with Disabilities Act is India’s version of the ADA but with little to no compliance.

Even with the infrastructure uncertain, the hosts evaluated the layout of each venue, built ramps and made sure the program was as accessible as possible. Tyler Ellis, a senior program associate at FHI 360, a global human-development organization, attended the event and was impressed by the program’s setup. “The college did an excellent job of setting up the rooms in a way that could accommodate all the participants, based on their varying abilities, which we all appreciated,” he told DJA.

During one part of the program, the players had a training session at Nehru Indoor basketball court where they were divided into three groups, each with an equal number of U.S. and India players. They were paired one-on-one, practicing drills, competitive strategies and sharing tips on best court practices.

Across the court, players rolled out to one another to work on their passes, layups, propelling at just the right speed or to simply stretch. With shouts of encouragement in English and Hindi from around the game, everyone could feel the excitement in the gymnasium.

The teams also played on outdoor concrete courts, a notable difference for U.S. players who are more accustomed to rolling on softer, spongier surfaces. Ellis highlighted differences in both countries’ wheelchair functionality – India’s hard and sturdy wheelchairs did not allow for as much mobility as the U.S. team’s frames and wheels which were designed for more dynamic movement and speed. “The University of Alabama in collaboration with PH International and FHI 360 organized eight wheelchairs from The University Alabama that were donated to team India. They were presented to each one of the team India players that were there for the clinic. I’m really proud of that element of the exchange,” Ellis told DJA.

On home soil, U.S. collegiate programs also leverage international connections to find elite athletes. It’s not rare, on an American team, to see athletes from Canada, the U.K., or Australia taking the court. And that’s where wheelchair basketball athletes tend to feel more at home: on the hardwood.

Gunasekaran felt that his athletes learned a lot from their visitors.

“These events help both countries’ teams see the real abilities and dreams of individuals with disabilities. This awareness naturally leads to much-needed accessibility solutions in society,” he said.

More DJA Coverage

Dr. Cynthia George — better known around Nashville’s punk scene as Dr. CynCorrigible — is impossible to miss....

By

October 23, 2025

As a Disability-led organization, we think it’s important to share the wealth. Here are five newsletters that we...

By

October 16, 2025

Aaron Kittredge via Pexels Donald Trump’s onslaught of cuts to federal services is now being directed at...

By

October 13, 2025